Introduction: clarity in the fog

I know. The world doesn’t need another article on Israel and Palestine — let alone from someone who isn’t a diplomat, historian, or war correspondent. But the thing is, most of what we already have either screams from one ideological trench or whispers from behind a moral fog. This isn’t that.

I’m writing this because clarity matters — and because I’ve watched too many smart people tie themselves in ethical knots, excusing terror, flattening complexity, or parroting slogans they’d never tolerate in any other context. I’m not here to take sides. I’m here to think — and to invite you to think too.

Since the events of October 7, 2023, the moral compass of much of the West seems to have spun out of control. Civilian massacres are reframed as resistance. Genocide is redefined at convenience. The same institutions that chant for human rights can no longer distinguish between defence and aggression, or between ideology and atrocity.

This isn’t a history lecture. It’s not a sermon either. It’s a timeline, yes — but also a reckoning. A walk through what’s happened, what’s been distorted, and what we’re no longer allowed to say out loud. You might not agree with all of it. That’s fine. But if you make it to the end, I hope you’ll agree it’s clearer than when you started.

Because if we can’t speak clearly about this — about murder, ideology, propaganda, and meaning — then we’re not just confused. We’re complicit.

Origins: before the state of Israel

The conflict did not begin in 1948, though that year marked a definitive rupture. To understand the present, we must look further back — to ancient claims, imperial legacies, rising nationalisms, and the slow, volatile unravelling of a fragile region.

Ottoman rule and the pre-mandate landscape

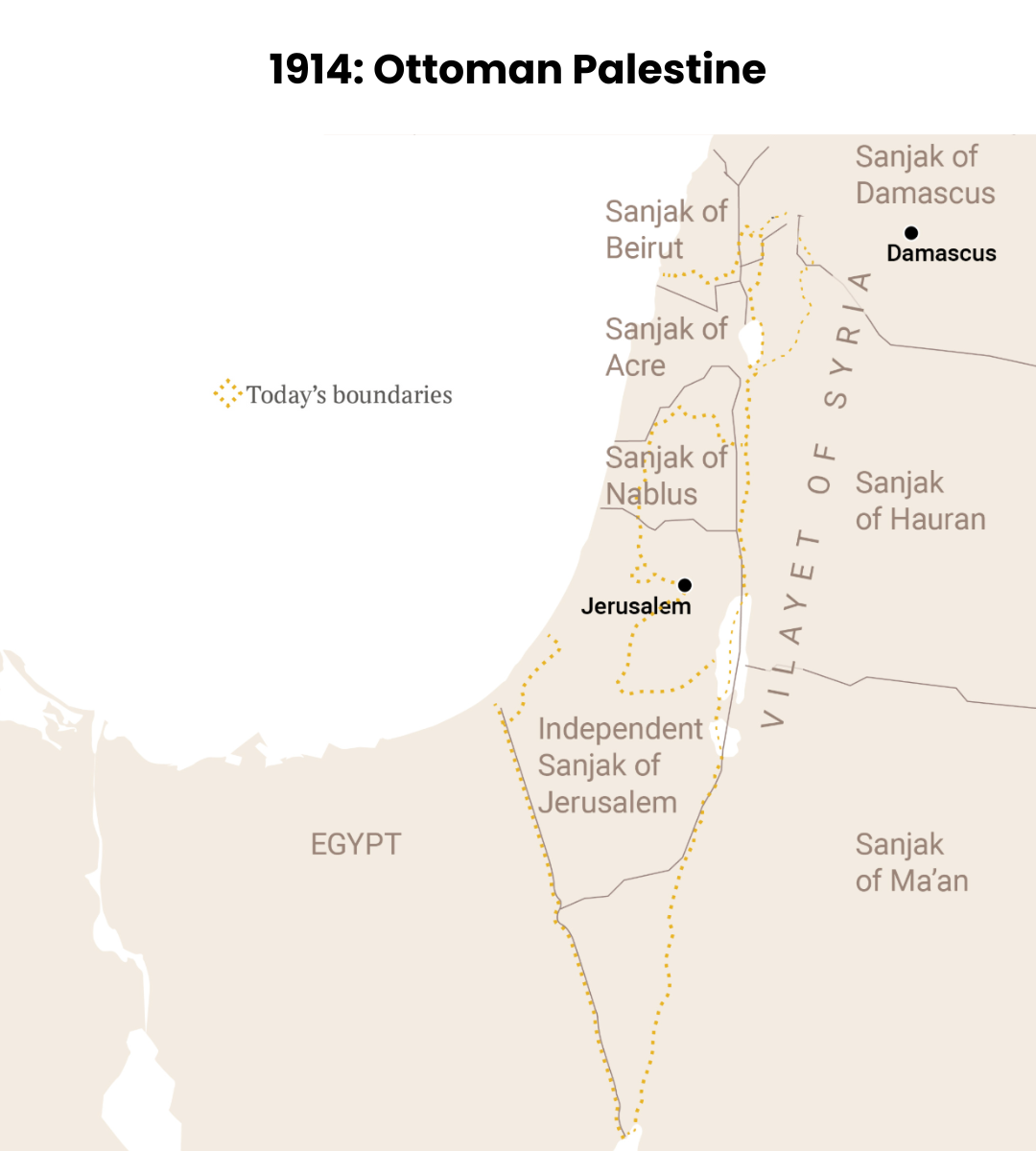

In the 19th century, what is now Israel, Gaza, and the West Bank was part of the sprawling Ottoman Empire. The region was divided into administrative districts, or sanjaks, including those of Jerusalem, Nablus, and Acre. Palestine was not a sovereign nation but a patchwork within larger provincial frameworks. It was home largely to Arabs — both Muslims and Christians — alongside a small but continuous Jewish minority.

Map: The Ottoman administrative regions of Palestine before World War I, showing sanjaks and today’s borders in dotted lines. Souce: Britannica.

During World War I, Arabs revolted against Ottoman rule, spurred on by Britain’s vague promises of Arab independence. At the same time, Britain and France had secretly agreed to divide the region through the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement — carving the Levant into future spheres of influence.

Balfour and the British mandate

In 1917, British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour sent a letter to Lord Rothschild expressing support for “a national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine — a move that would become the basis for Zionist aspirations. However, the same letter promised not to prejudice the rights of “existing non-Jewish communities.”

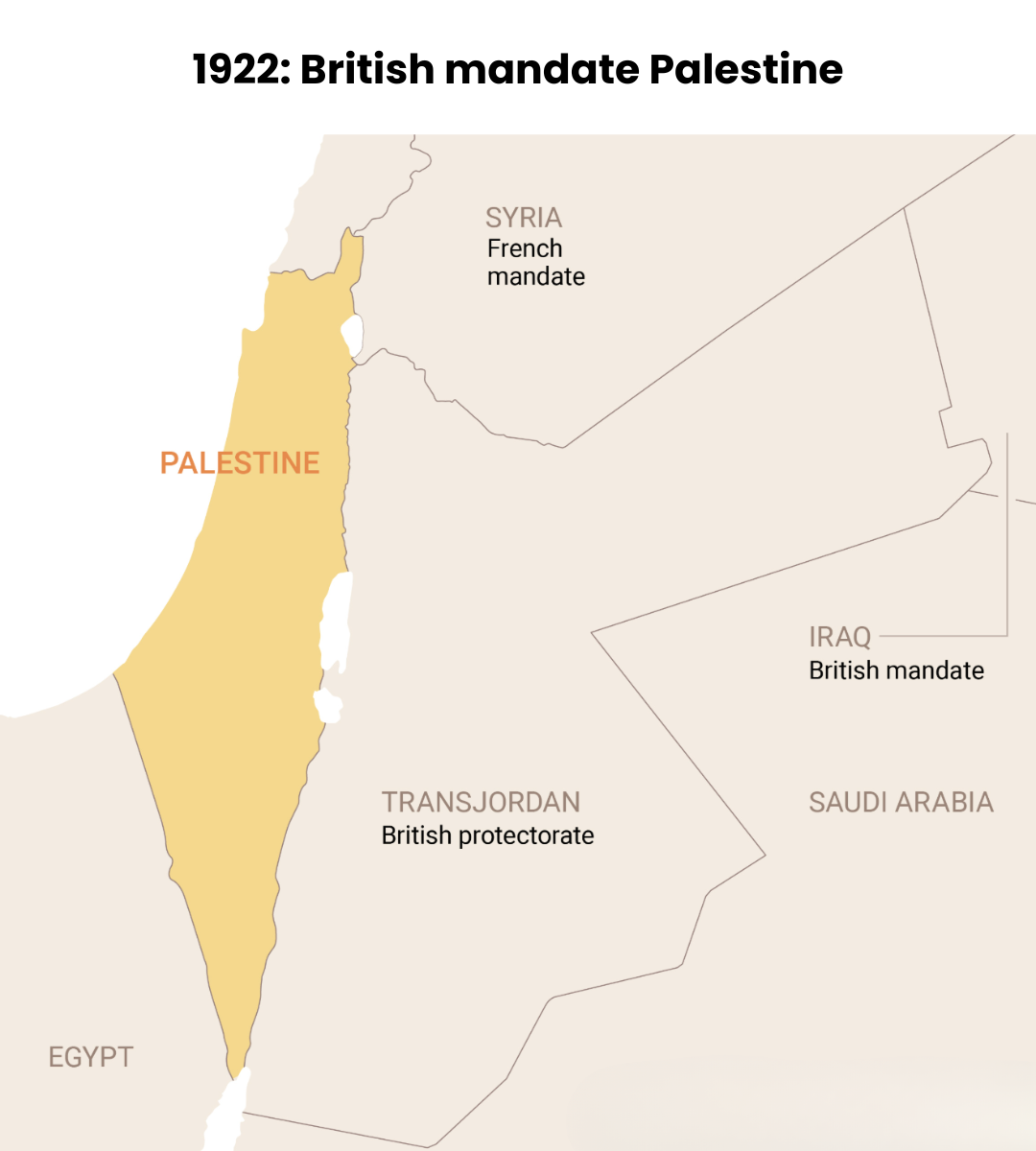

By 1922, the League of Nations had handed Britain formal control over Palestine. Jewish immigration — mostly from Eastern Europe — accelerated, especially in the 1930s, fuelling Arab resentment and fear of displacement. Riots, massacres, and uprisings followed.

Map: Palestine under British control, with neighbouring protectorates and mandates carved from the Ottoman Empire. Souce: Britannica.

Winston Churchill, then colonial secretary, attempted to calm tensions by limiting Jewish immigration and clarifying that Palestine was not to become a Jewish state — while reaffirming the Balfour Declaration. His balancing act satisfied no one. Arab nationalism surged. Jewish refugees kept coming.

Partition and catastrophe

By the end of World War II and the Holocaust, international sympathy for the Jews had reached a critical mass. The British, overwhelmed by violence and diplomatically cornered, referred the issue to the newly formed United Nations.

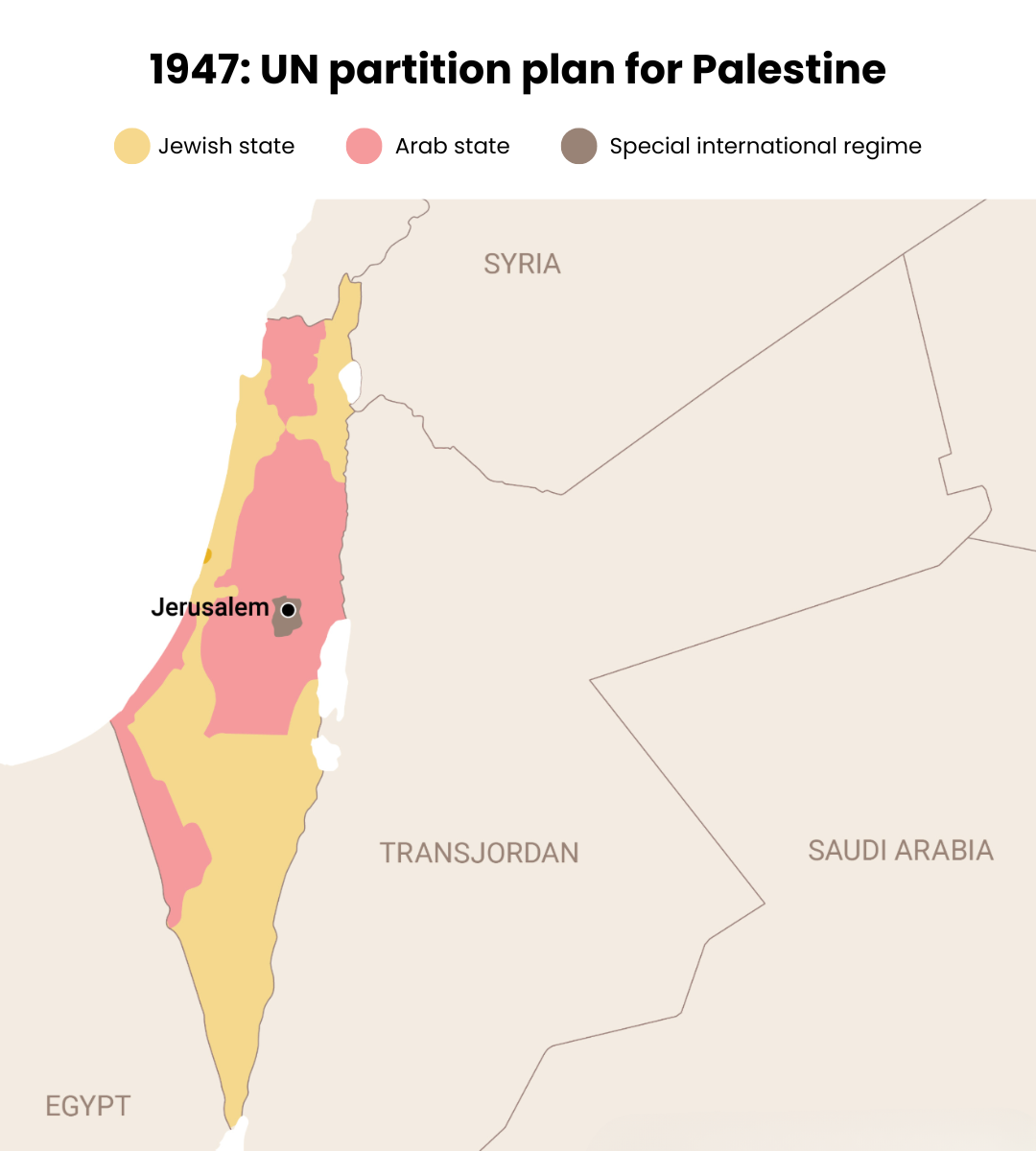

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly passed a partition plan to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem under international administration. The Jews accepted it. The Arabs rejected it. War began immediately.

Map: The UN’s proposed partition — yellow for the Jewish state, red for the Arab state, and brown for Jerusalem’s international status. Souce: Britannica.

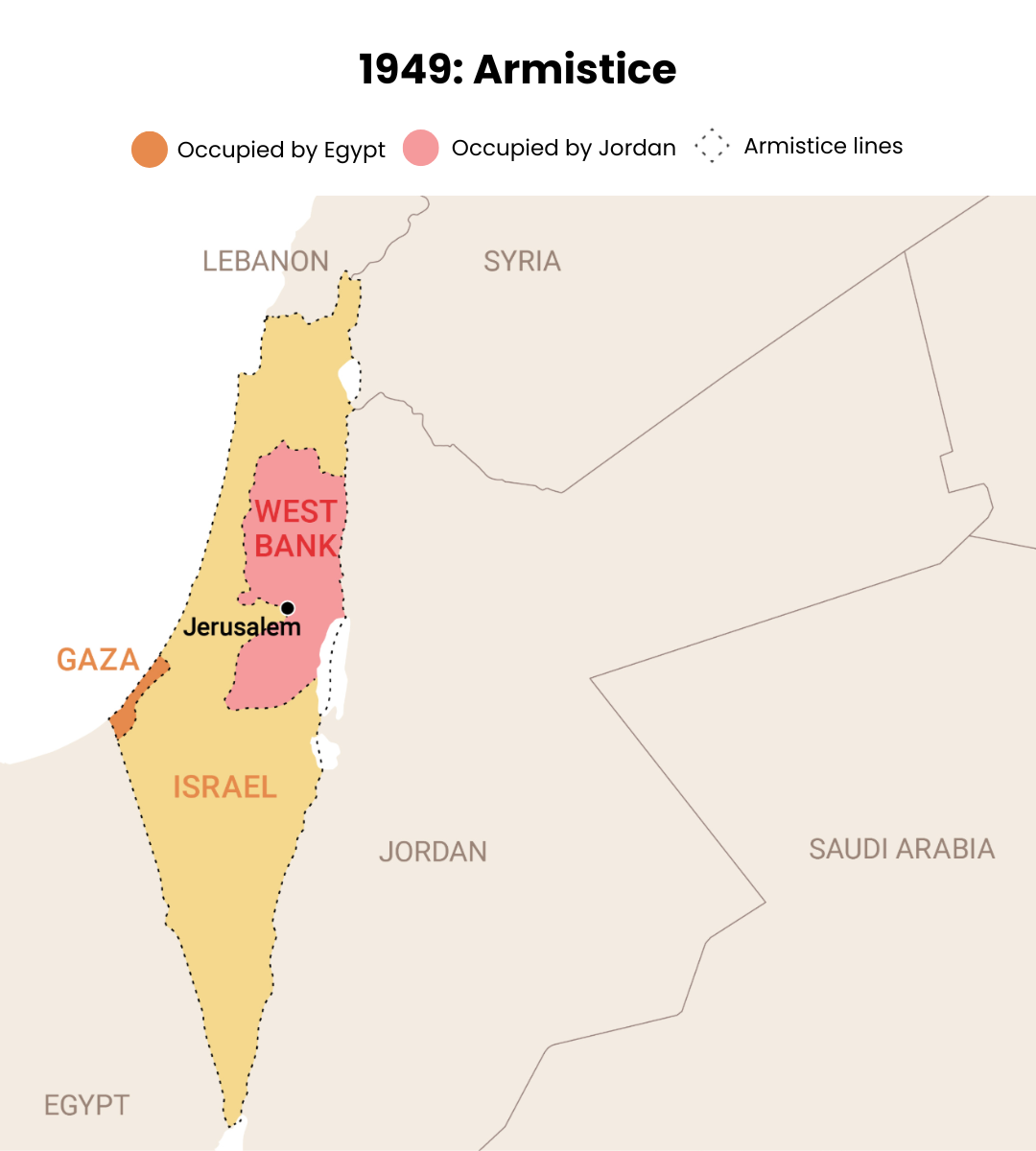

On May 14, 1948, David Ben-Gurion declared the establishment of the State of Israel. Within hours, five Arab states invaded. Israel pushed them back and secured territory beyond the UN allocation. By 1949, new borders were drawn — and over 700,000 Palestinians were displaced. This is what Palestinians call the Nakba — the catastrophe.

Map: Post-war borders. Israel expanded beyond the UN plan, while Egypt occupied Gaza and Jordan annexed the West Bank. Souce: Britannica.

This prelude matters because it reveals that the conflict is not merely territorial, but historical, emotional, and existential. It cannot be understood through slogans or resolved through sentiment. It is a collision not just of peoples, but of pasts.

Timeline: Key events in the Israel-Palestine conflict — 1948–2023

What happened next: October 7 and the moral fracture

The events of October 7, 2023, marked a rupture — and the reckoning hasn't stopped since. Not only on the battlefield, but in classrooms, on newsfeeds, and in the corridors of power across the West. What we’re witnessing isn’t just a war in Gaza — it’s a collapse of moral clarity in the societies watching from afar.

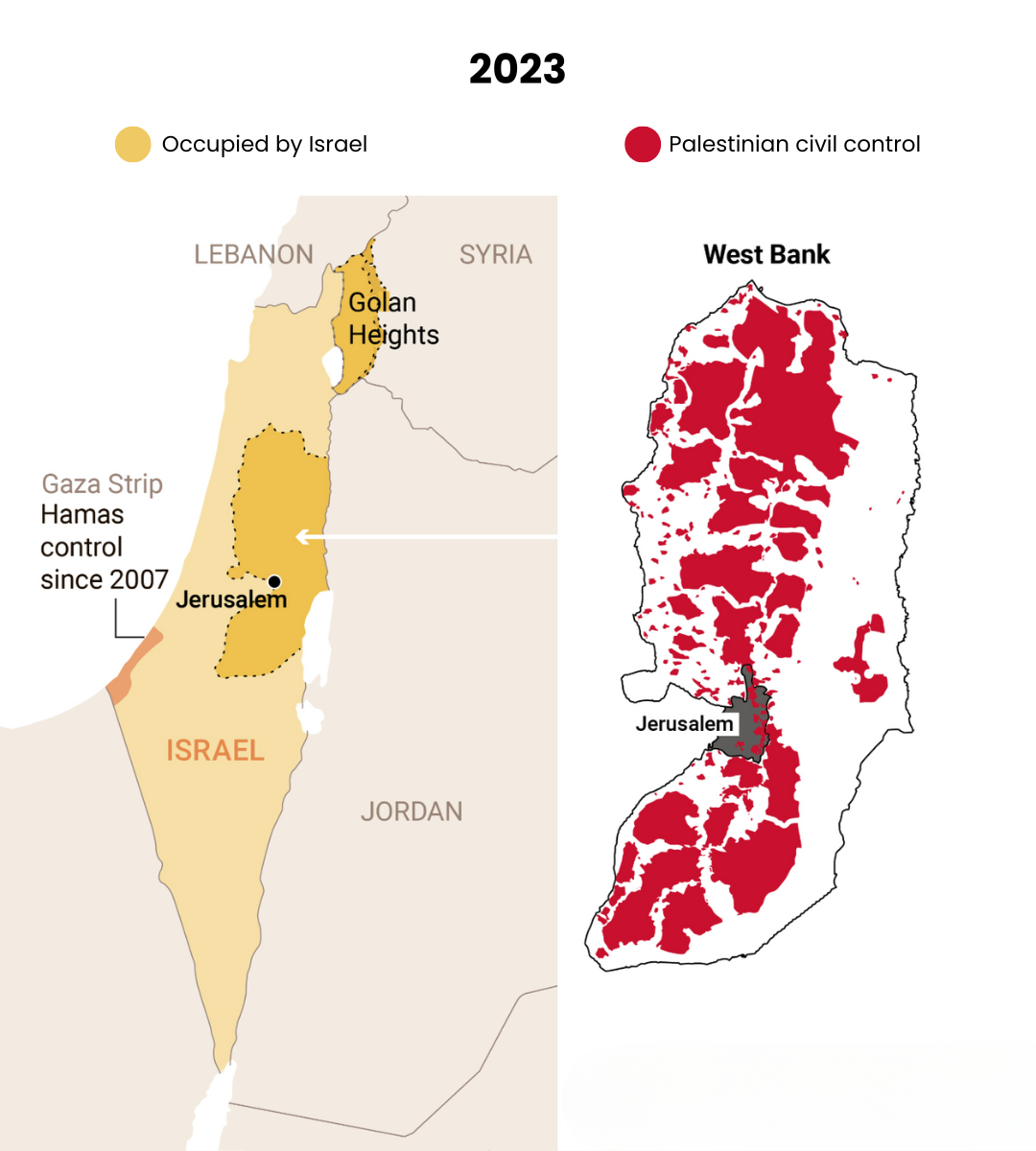

Map: By 2023, Gaza was under Hamas control, the West Bank fragmented under Israeli occupation and partial Palestinian civil administration, and Jerusalem remained disputed. Source: Britannica

In the wake of Hamas’s atrocities, many institutions — universities, NGOs, media outlets — responded not with unequivocal condemnation, but with evasions, false equivalencies, or worse: applause. “Resistance” became the euphemism of choice. Calls to “contextualise” terrorism were louder than calls to reject it. The most shocking thing wasn’t the violence itself — but how quickly many people forgot what violence actually is.

But the reckoning didn’t stop there. As Israel began its campaign to dismantle Hamas, the scale and intensity of its response triggered another crisis of conscience. Civilian death tolls soared. Entire neighbourhoods were flattened. Gaza’s hospitals, schools, and refugee camps became targets of war. By 2025, major human rights groups and UN officials were accusing Israel of committing genocidal acts. Israel denied the charges — but the images told a different story.

Gaza City in ruins following Israeli airstrikes, months into the war. What began as retaliation has become a landscape of devastation — and a global symbol of both grief and polarisation.

Once again, clarity fractured. To some, Israel’s response looked like self-defence against an existential threat. To others, it was the deliberate destruction of a civilian population. Between those views, the truth struggled to survive — squeezed by politics, online tribalism, and the long shadow of historical trauma.

In the West, ideological fault lines hardened. One side saw barbarism and responded with mourning. The other saw a narrative opportunity and responded with hashtags. And then the roles reversed. Neither side held a monopoly on grief. But both sides proved how easily grief can be politicised.

This moral fracture is no longer just about Israel and Gaza. It’s about us — about the West’s memory, its values, and its increasing inability to judge clearly when tribal instinct overwhelms moral reasoning. Because the deeper conflict isn’t only in Gaza. It’s in how we think, speak, and respond. And in that theatre, too, we are failing the test.

Israel–Palestine: 10 key questions answered

From Hamas to Zionism, genocide claims to peace prospects — a clear-eyed FAQ for those trying to understand the conflict without the noise.

Who is Hamas, and what do they believe?

Hamas is a Palestinian Islamist organisation founded in 1987 as an offshoot of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. Its name is an acronym for “Islamic Resistance Movement.” Hamas has a military wing and a political wing, both of which have gained power in the Gaza Strip since the early 2000s. It is designated as a terrorist organisation by Israel, the U.S., EU, and others.

Its 1988 charter openly called for Israel’s destruction and framed the conflict as a religious war. While a later document in 2017 softened some language, it did not renounce armed struggle or recognise Israel. Hamas blends Palestinian nationalism with jihadist ideology — and governs Gaza through authoritarian control. To call it a resistance movement without noting its death-cult rhetoric and strategy is to mistake violence for virtue.

Where does America stand, and why?

The United States has been Israel’s closest ally since the Cold War — a relationship cemented by military aid, intelligence sharing, and deep diplomatic ties. Strategic interests in the Middle East play a part, but so do shared values and powerful domestic lobbies that make unwavering support for Israel a political default.

But the consensus is fracturing. While Republicans remain firmly pro-Israel, parts of the Democratic Party — especially its progressive wing — have turned sharply critical, framing Israel as a colonial aggressor or apartheid regime. This internal rift has deepened since October 7.

President Biden tried to hold the centre: affirming Israel’s right to self-defence while calling for restraint. But in a hyper-polarised America, even nuance reads like betrayal to one side — or cowardice to the other.

How reliable are the casualty figures from Gaza?

Most casualty figures from Gaza come from the Gaza Health Ministry — an arm of Hamas. International bodies like the UN and WHO often cite these numbers, but they’re not independently verified, and they typically don’t distinguish between civilians and fighters. Critics argue the figures are likely inflated or shaped for propaganda.

That doesn’t mean the suffering isn’t real. Thousands have died, many of them civilians. The challenge is how we talk about it: without accepting numbers uncritically, and without downplaying the human cost. Hamas has every incentive to amplify civilian deaths for sympathy. Israel has a duty to avoid them. Both can be true. And both matter.

Why is Israel accused of apartheid?

Some human rights groups (e.g. Amnesty, Human Rights Watch) and UN figures accuse Israel of apartheid — a system of domination and segregation. They cite restrictions on Palestinian movement, different legal systems in the West Bank, and the unequal treatment of Arab citizens of Israel.

Israel and its defenders argue that this comparison is false and inflammatory. Arab citizens of Israel vote, serve in parliament, and access civil rights — unlike the apartheid system in South Africa. The West Bank, they argue, is a disputed territory under temporary military control, not part of sovereign Israel. Whether one agrees or not, the term is politically loaded and often used less to describe than to delegitimise.

What are Israeli settlements, and why are they controversial?

Israeli settlements are Jewish communities built in the West Bank and East Jerusalem — territories captured in the 1967 war. Many in the international community consider them illegal under the Fourth Geneva Convention, though Israel disputes this.

Critics say settlements fragment the land, making a viable Palestinian state impossible. Supporters argue that Jews have historical and legal claims to these areas, and that some settlements are strategically necessary. The issue goes beyond real estate: it’s about identity, legitimacy, and the future of the two-state solution.

Why don’t Arab states support the Palestinians more directly?

While many Arab governments rhetorically support Palestine, actual support has been inconsistent. Some states — like Jordan and Egypt — have made peace with Israel. Others — like Saudi Arabia and the UAE — have pursued quiet or open normalisation, especially since the Abraham Accords.

Reasons vary: fear of Islamism (especially Hamas), fatigue with internal Palestinian divisions, strategic alignment against Iran, or desire for Western favour. Palestinian leadership has often been mistrusted or marginalised in these calculations. The Arab world is not a monolith, and pan-Arab solidarity has long given way to realpolitik.

What is Zionism — and how has it been misrepresented?

Zionism is the belief in Jewish self-determination in their ancestral homeland. It emerged in the late 19th century as a secular, political movement in response to rising antisemitism in Europe. For most Jews, it means the right to a safe and sovereign state — not supremacy over others.

Critics have recast Zionism as inherently racist or colonialist. But this conflates a national liberation movement with imperialism, ignoring Jewish indigeneity, trauma, and exile. Like any nationalism, Zionism can be corrupted by extremism. But opposing Zionism in principle often slides into denying Jews the very right that other peoples are assumed to have.

What is the two-state solution, and is it still possible?

The two-state solution proposes an independent Palestine alongside Israel, based on pre-1967 borders with agreed land swaps. It was the core of the Oslo process in the 1990s and remains the international consensus.

But on the ground, the prospects look grim. Settlements have expanded, trust has collapsed, and Palestinian politics are divided between Fatah and Hamas. Some now call for a one-state model, but few believe it’s viable or desirable. Still, for many, two states remain the least bad option — not because it’s perfect, but because the alternatives are worse.

Why does this conflict provoke such intense global emotion?

Unlike other wars, this one touches on religion, identity, trauma, and ideology. It plays out live on social media. It maps neatly — too neatly — onto Western political binaries. The Holocaust. Islamophobia. Colonialism. Resistance. Terrorism. Everyone sees their own story in it.

That emotional charge is what makes the conflict so manipulable. Symbols replace facts. Slogans override nuance. Grief gets instrumentalised. And complexity is flattened into morality plays. This is no accident — it’s how propaganda works.

Why is peace so hard to achieve — and what would it take?

Because both sides have real grievances, bad-faith actors, internal divisions, and histories of trauma. Because power is uneven, narratives are weaponised, and peace is rarely profitable in the short term. Because bad timing, political cowardice, and violence have killed deal after deal.

What would it take? Leadership. Compromise. Security guarantees. An international community willing to hold all sides accountable. And a moral culture willing to reject both antisemitic and anti-Arab hate — and resist the seductive pull of tribal certainty. Until then, peace remains a slogan. But it doesn’t have to be.

The regional web: who else is involved — and why it matters

This isn’t just a fight between Israelis and Palestinians. Behind the headlines is a web of regional power struggles, ideological alliances, and geopolitical manoeuvring. To understand the conflict clearly, we need to look at the forces sustaining it — and exploiting it.

Iran

Iran is the most significant external actor in the current conflict. It funds, trains, and arms Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and Hezbollah. Its goal isn’t Palestinian liberation — it’s the strategic encirclement of Israel and the export of the Islamic Revolution. Tehran doesn’t just want influence. It wants leverage — and Gaza is one of its pressure points.

Qatar

While presenting itself as a neutral mediator, Qatar has long hosted Hamas leaders and funded civilian infrastructure in Gaza. Critics argue it provides political cover and financial lifelines to a terrorist organisation. Supporters claim it maintains stability and facilitates dialogue. In truth, it does both — and its role is increasingly controversial.

Hezbollah and Lebanon

To Israel’s north, Hezbollah looms as a far more dangerous foe than Hamas. Backed by Iran and armed with an estimated 150,000 rockets, it represents the biggest conventional military threat to Israel. Clashes on the Lebanese border remain a constant flashpoint, and any major escalation could lead to all-out war.

The Houthis

From Yemen, the Iran-backed Houthis have launched drone and missile attacks on Israel and disrupted global shipping in the Red Sea. These actions are framed as solidarity with Gaza — but they also serve Tehran’s broader goal of destabilising Western-aligned trade and security networks.

The United States

America remains Israel’s most important ally. It provides billions in military aid and diplomatic cover. But the domestic political landscape is shifting. Younger progressives increasingly criticise Israel, while Republicans remain firmly pro-Israel. Biden tried to straddle both positions — backing Israel’s right to defend itself while urging restraint. The result is a growing rift within the Democratic Party.

The Arab World

Publicly, Arab states condemn Israeli actions. Privately, many are tired of the Palestinian issue. Egypt and Jordan have peace treaties with Israel. Saudi Arabia was on the brink of normalisation talks before October 7. These governments fear Iran, loathe Hamas, and prioritise stability. Their outrage is often performative — a diplomatic mask for strategic disinterest.

Turkey, Russia, China

Turkey has positioned itself as a champion of the Palestinian cause, but its posture is more populist than practical. Russia sees the conflict as an opportunity to divide the West, while China plays the long game — calling for peace, but investing in both sides. None of these powers want resolution. They want advantage.

Language, propaganda, and the death of meaning

Wars are fought with weapons, but also with words. And in the Israel–Palestine conflict, language is no longer descriptive — it’s ideological.

Terms like “genocide,” “resistance,” “colonialism,” and “apartheid” aren’t used to explain. They’re used to accuse. Not to clarify, but to condemn. These words have become rhetorical grenades — stripped of context, lobbed across digital battlefields with moral certainty and zero restraint.

In this new linguistic landscape, "resistance" can mean anything — even the murder of children. "Genocide" is redefined to suit the narrative. "Occupation" is applied in blanket terms, regardless of context. And the word "terrorism" has all but disappeared from some coverage, replaced by more palatable euphemisms. Meanwhile, terms like “ceasefire” and “proportionality” are weaponised as political cudgels rather than legal concepts.

This isn’t just semantics — it’s strategy. Propaganda thrives on emotionally charged but intellectually hollow language. If everything is apartheid, then nothing is. If everyone is a coloniser, then no one is. These distortions flatten moral reality and make critical thinking feel like betrayal.

Social media accelerates the decay. On X, TikTok, and Instagram, moral complexity doesn’t go viral — outrage does. Algorithms reward certainty, not subtlety. And so we drift into a world where meaning collapses under the weight of performance.

What’s lost is the ability to think clearly. If every word is loaded, and every label is moral theatre, then reasoned disagreement becomes impossible. We stop debating ideas and start defending identities. And once that happens, the truth is no longer something we seek — it’s something we accuse others of hiding.

In this conflict, as in so many others, clarity isn't just rare — it’s dangerous. Because clarity demands judgment. And judgment, in this age of tribal certainties, is the one unforgivable sin.

Final reflections: The cost of clarity

We live in an age where tribal identity often overrides moral reasoning. Where ideology blurs the line between victim and aggressor. Where historical amnesia and selective outrage create a carousel of false equivalencies. And where asking for context — or offering it — is treated as complicity.

But clarity is not complicity. It’s a refusal to lie — or be lied to.

You don’t have to choose between compassion for Palestinians and condemnation of Hamas. You don’t have to support everything Israel does to support its right to exist. And you don’t have to surrender your judgment to slogans, hashtags, or algorithms. You are allowed to think. In fact, you must.

Because if we can’t think clearly about this — about violence, ideology, history, and truth — then what hope do we have of thinking clearly about anything?

There is no virtue in confusion. No nobility in euphemism. And no peace in propaganda.

There’s only the long, difficult, necessary task of seeing — and saying — what is true.

Further reading and sources

Jerusalem: The Biography by Simon Sebag Montefiore

A sweeping, vivid account of the city's 3,000-year history — religious epicentre, battleground, and symbol. Essential for anyone seeking to understand the sacred geography at the heart of the conflict.

The Iron Cage: The Story of the Palestinian Struggle for Statehood by Rashid Khalidi

A critical yet empathetic history of Palestinian nationalism and its many missed opportunities — from British colonial rule to the Oslo Accords.

My Promised Land: The Triumph and Tragedy of Israel by Ari Shavit

A deeply personal, morally complex account of modern Israel from a liberal Zionist journalist grappling with the beauty and contradictions of his homeland.

Hamas: Politics, Charity and Terrorism in the Service of Jihad by Matthew Levitt

An in-depth investigation of Hamas’s dual structure — social movement and militant group — and how its ideology drives its political strategy and military campaigns.

The War for Muslim Minds: Islam and the West by Gilles Kepel

A thoughtful exploration of political Islam post–9/11 and how the battle between moderates and extremists within the Muslim world has global consequences.

The Case for Democracy by Natan Sharansky

A passionate argument from a former Soviet dissident that freedom, not realpolitik, is the only reliable path to peace — especially in the Middle East.

The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 by Christopher Clark

A masterful account of the complex web of misjudgments and rivalries that led to the First World War — and a sobering reminder of how great powers can sleepwalk into catastrophe.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking articles. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.

You might also like: