There’s a particular kind of exhaustion setting in across the West. Not the exhaustion of physical labour or economic hardship — though those are real enough — but something deeper, more disorienting. A psychological fatigue that comes from living too long inside a narrative that doesn’t make sense, but that you’re still expected to repeat as if it does.

The term “gaslighting” has become a cliché, tossed around on social media with such frequency that it risks losing its force. But its origins are worth revisiting. In Gaslight, the 1944 film adaptation of Patrick Hamilton’s play, a man manipulates his wife into doubting her own sanity by dimming the lights in their home and then insisting nothing has changed. It is not just lying — it is lying with such confidence and relentlessness that the victim begins to question the evidence of her own senses.

There is something eerily familiar about that dynamic today.

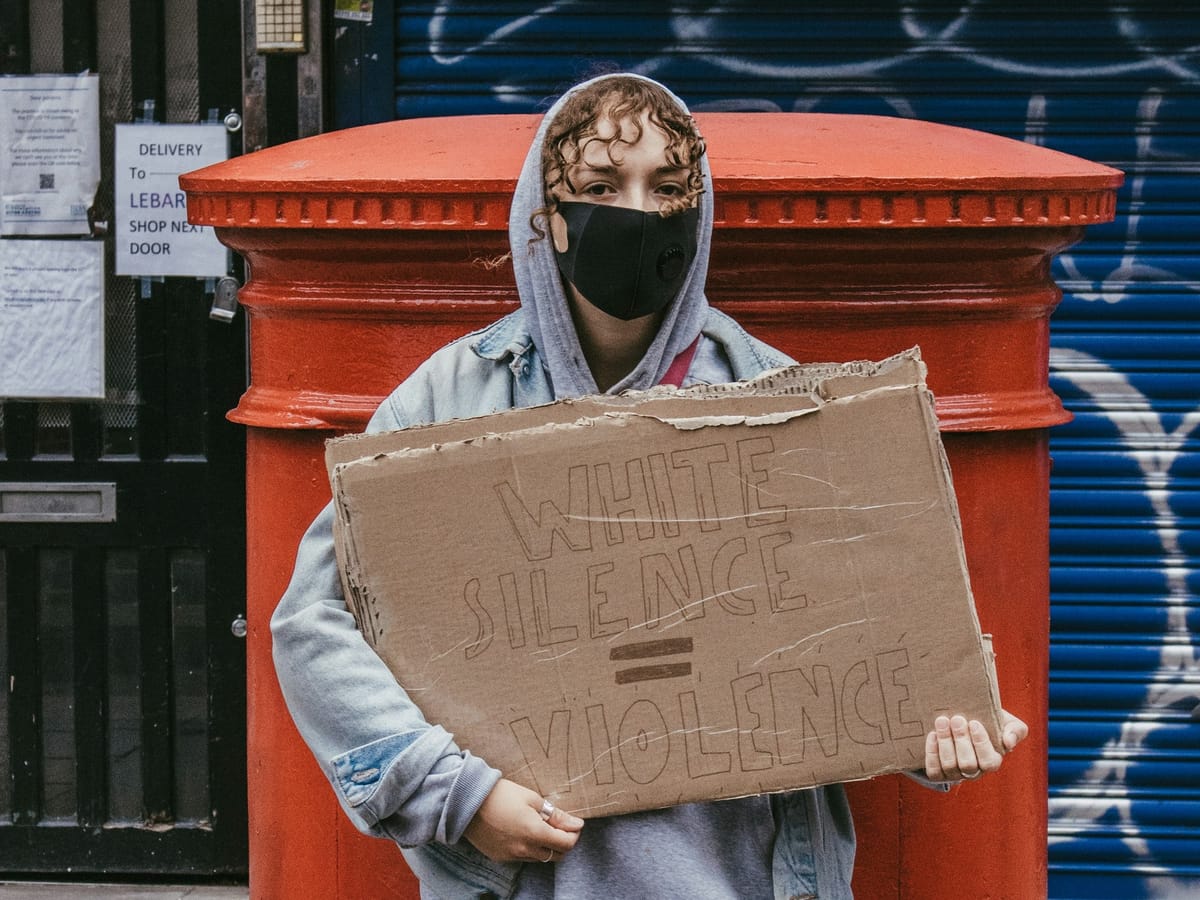

We are told — not asked, told — that men can get pregnant, that maths is racist, that the phrase “I don’t see colour” is itself a form of white supremacy. We are informed that words are violence, that silence is violence, and that actual violence — such as riots or looting — can be redefined as “mostly peaceful protests.” During the Covid pandemic, government messaging became a case study in institutional gaslighting: masks didn’t work until they did, lockdowns were a public health imperative until they weren’t, dissent was a public danger until it wasn’t. Each reversal came with the same unblinking certainty as the last.

This isn’t merely confusion. It’s manufactured confusion — a deliberate, or at least convenient, fog.

Islamist extremism presents a similar paradox. In the wake of attacks, citizens are told that the ideology behind them is irrelevant — or that to even suggest a link is to stigmatise an entire community. Thus, the act of noticing becomes the greater sin. A society that cannot say what it sees is a society primed for manipulation.

Think better. Get the FREE guide.

Join Veridaze and get 10 Mental Tools for Clearer Thinking — a free guide to cutting through noise, confusion, and nonsense.

Meanwhile, in the classroom, students are taught that knowledge is a colonial construct, that objectivity is a tool of oppression, and that lived experience trumps observable reality. In the corporate world, entire departments exist to ensure ideological compliance — equity officers, sensitivity trainers, bias auditors — all with the power to punish deviation from approved scripts. Say the wrong thing, even accidentally, and you may lose your job. Say the right thing, and you may not believe it — but at least you’ll be safe.

This epistemic chaos is not confined to the UK. It is a Western malaise. A kind of societal gaslighting, in which power no longer resides in truth but in the capacity to make truth elastic — to reshape it, weaponize it, and, if necessary, erase it. The culture wars are the flare-ups; the deeper infection is a loss of shared reality.

Of course, not all of this is intentional. Many of the individuals driving these narratives are sincere — and that’s part of the danger. Useful idiocy and moral fervour make for a potent mix. But if I were looking to undo a nation — to soften its institutions, fragment its people, and obscure the line between sense and nonsense — this would be an excellent place to start. Flood the discourse with unreality. Punish dissent. Praise conformity. Watch the centre collapse.

That’s what makes gaslighting such a powerful weapon. It doesn’t have to convince everyone — just enough people to create a fog of uncertainty, where saying nothing becomes safer than saying something true. In that space, real power thrives.

And yet, in all this madness, a strange hope endures. Because the very act of naming the madness — of saying, “no, the lights have dimmed” — is an act of resistance. It’s a signal to others, often silent, that they are not alone. That clarity is still possible. That the centre can hold, if only we choose to see clearly, speak plainly, and refuse to play along.

Further reading

The Madness of Crowds by Douglas Murray

A sharp and controversial look at how identity politics, ideology, and mass hysteria have disrupted rational discourse.

The Coddling of the American Mind by Jonathan Haidt and Greg Lukianoff

Explores how well-intentioned ideas — like safetyism and emotional reasoning — are undermining resilience and critical thought in the West.

Manufacturing Consent by Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky

A foundational text on media manipulation, showing how power structures shape public perception and restrict the range of acceptable thought.

Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell

Still the definitive literary treatment of gaslighting as a system of control — terrifyingly relevant in the digital age.

The Status Game by Will Storr

Examines how status dynamics shape human behaviour — and how ideologies become vehicles for virtue, dominance, and social control.

The Psychology of Totalitarianism by Mattias Desmet

An exploration of mass formation and collective delusion in modern societies — with controversial yet timely parallels to Covid-era policy.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking articles. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.

You might also like: