It’s not stupidity driving the populist revolt — it’s exhaustion.

As Janice Turner argued in The Times, the people turning to Reform UK aren’t confused or radicalised. They’re simply tired of being patronised by the people who run the country as if it were a conference. Tired of the lectures. Tired of being spoken to in risk-assessed jargon by those who’ve never had to worry about the price of petrol or a missed GP appointment. The lanyard class, as Turner aptly calls them, is losing its grip — not because the public has lost its mind, but because it’s finally lost patience.

The lanyard itself has become a kind of class marker — not just of employment but of worldview. It signals membership of a credentialed caste fluent in HR protocols, diversity audits and procurement language, but tone-deaf to the rhythms of ordinary life. These aren’t villains. They’re administrators, managers, facilitators. They mean well (they never stop telling us). But they govern with laminated values, not moral courage. And the results speak for themselves.

Crime is “down,” they insist, as everyone watches shops ransacked in daylight. Housing is a “priority,” while your grown children can’t afford to leave home. Migration is “enriching,” though your local surgery has a three-week wait and no one speaks English in the waiting room. It’s all being managed, you’re told. But what you see is slow decay. What you hear is the voice of someone who's never had to live with the consequences. As economist Thomas Sowell once remarked, “It is hard to imagine a more stupid or more dangerous way of making decisions than by putting those decisions in the hands of people who pay no price for being wrong.”

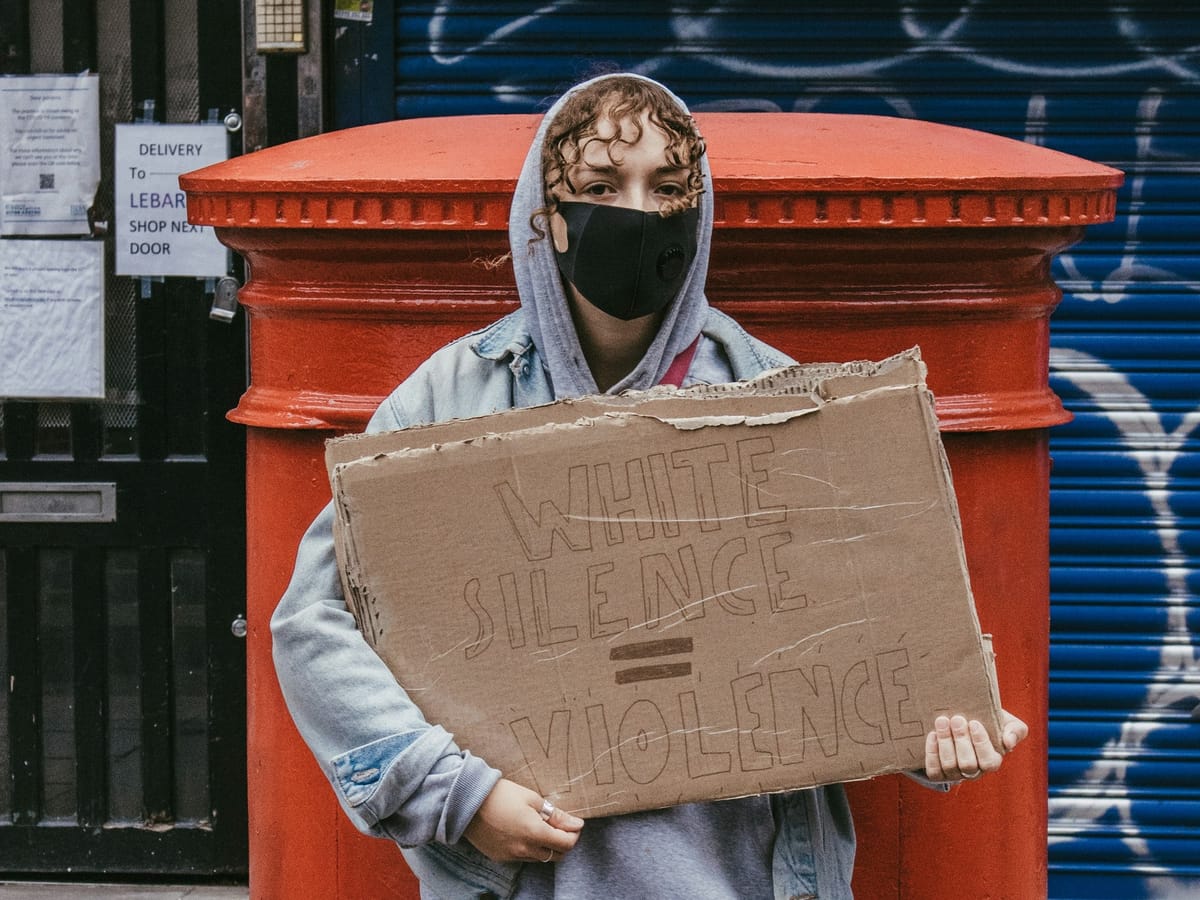

What frustrates people is not just the gulf in lifestyle — it’s the cultural arrogance. This class has replaced moral reasoning with performance, delivery with optics. They know the correct hashtags, wear the correct ribbons, display the correct flags. But ask why a nurse earns less than an NHS diversity officer, or why public money is vanishing into management roles with no measurable outcomes, and they look at you like you’re the problem.

Think better. Get the FREE guide.

Join Veridaze and get 10 Mental Tools for Clearer Thinking — a free guide to cutting through noise, confusion, and nonsense.

This is the paradox of the lanyard class: they claim to listen, but only if you’re speaking their language. Raise concerns about immigration or crime, and you’re “dog-whistling.” Mention biological sex, and you’ve committed a hate incident. Try to describe the world as you actually live it, and you’ll be told, with barely concealed condescension, that you’ve misunderstood reality.

Too often, democratic dissent is pathologised. Frustration is recast as hate, concern treated as extremism, and populism dismissed as either a moral failing or a cognitive defect. It’s easier, it seems, to sneer at voters than to ask what they’re voting against. And while this is often cloaked in the language of moral universalism, today’s version flows in only one direction — selective in its compassion, ruthless in its judgement, and blind to its own hypocrisies. It is not principle but performance. A status game dressed up as virtue, as Will Storr has argued with brutal clarity.

Instead of confronting the real sources of discontent — failing services, rising crime, porous borders — those in power cling to narrative control. But the more reality diverges from the official script, the more inevitable the backlash becomes.

The lanyard class believe themselves benevolent — and perhaps they are, in intent. But like all elites, they eventually develop a reflexive disdain for those beneath them — a democratic disdain so internalised it no longer feels like ideology, just “the sensible centre.” Yet it is precisely this smug centrism — this culture of polished indifference towards what voters are actually saying — that has brought us here.

Consider the scandal of Britain’s grooming gangs. For years, ordinary people raised concerns. They were silenced by the very institutions tasked with protecting them, not out of ignorance, but because listening would have been awkward. Because reputational risk outweighed child safety. Because the optics mattered more than the outcome. It is one of the darkest illustrations of what happens when procedure trumps principle, and public trust is treated as a PR issue to be managed, not earned.

What we are seeing now is a correction — perhaps messy, perhaps imperfect, but morally justified. The public has noticed that the people who speak most about justice often deliver the least of it. That behind every laminated badge is someone who claims to know better, yet presides over worse.

Reform may be crude, but its rise is a referendum on the failure of the people who think they’re too clever to fail. The lanyard class thought it could manage discontent through consultation forms and compliance frameworks. But you cannot audit your way out of decline. You cannot pilot-scheme your way back to reality. And you cannot suppress half the country without them, eventually, answering back.

The revolt is not irrational. It is rational. It is democratic. And it is long overdue.

Further reading

The Road to Somewhere – David Goodhart

A sharp analysis of the divide between the mobile, educated “Anywheres” and the rooted, traditional “Somewheres” — a vital frame for understanding the rise of populism and class-based resentment.

The Status Game – Will Storr

Explores how human beings seek status through virtue, success, and dominance — and how modern moral signalling often masks deeper insecurities and power plays.

Democracy and Its Crisis – A.C. Grayling

An urgent call to rethink how Western democracies have drifted from their foundations, leaving citizens feeling voiceless, alienated, and disrespected.

Head, Hand, Heart – David Goodhart

Argues that Western societies have over-rewarded cognitive ability (“head”) at the expense of practical and caring labour — fuelling resentment and social division.

The Revolt of the Public – Martin Gurri

Charts how digital technology has empowered the masses to challenge elite narratives — and why institutions are struggling to adapt to a new age of transparency and rebellion.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking articles. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.

You might also like: