We often imagine tyranny as something obvious – a raised voice or a clenched fist; orders barked from behind riot shields. But some of the most dangerous forms of control don’t arrive with fanfare or menace. They present themselves in softer tones through appeals to safety, care, decency and the good.

We don’t usually associate words like “compassion” or “kindness” with authoritarianism. And yet, when those virtues become tools of governance rather than personal ethics — when they harden into mandates enforced by the state, the platform, or the school — something curious happens. The voluntary becomes compulsory. Dissent becomes deviance. And liberty begins to erode, not under pressure from cruelty, but under the slow, suffocating weight of someone else’s good intentions.

During the Covid years, we witnessed the emergence of this dynamic with unusual clarity. What began as a justified response to a global emergency gradually shifted into something more troubling. Even as the rationale for many restrictions weakened, the moral certainty with which they were enforced seemed only to strengthen. To question lockdowns or school closures was to be accused of selfishness. To express doubt about masking or mandates was to risk moral disgrace.

Few leaders embodied this shift more completely than Jacinda Ardern. As Prime Minister of New Zealand, Ardern became the global face of pandemic-era compassion. Her “be kind” slogan was widely admired. She spoke with warmth, offered reassurance, and projected a kind of moral serenity that seemed to transcend politics. But as her recent memoir A Different Kind of Power reveals — perhaps unwittingly — kindness, when coupled with power, can take on a very different character.

Critics of Ardern, like Jamie Whyte in The Times,, have pointed out what the former Prime Minister omits: the costs of her government’s prolonged lockdowns, the suppression of dissenting views, the growing paternalism of a state that increasingly demanded not just obedience, but moral alignment. Her governance, presented as empathetic, became in practice a form of ideological coercion — and it is here that a much older warning begins to resonate with disturbing clarity.

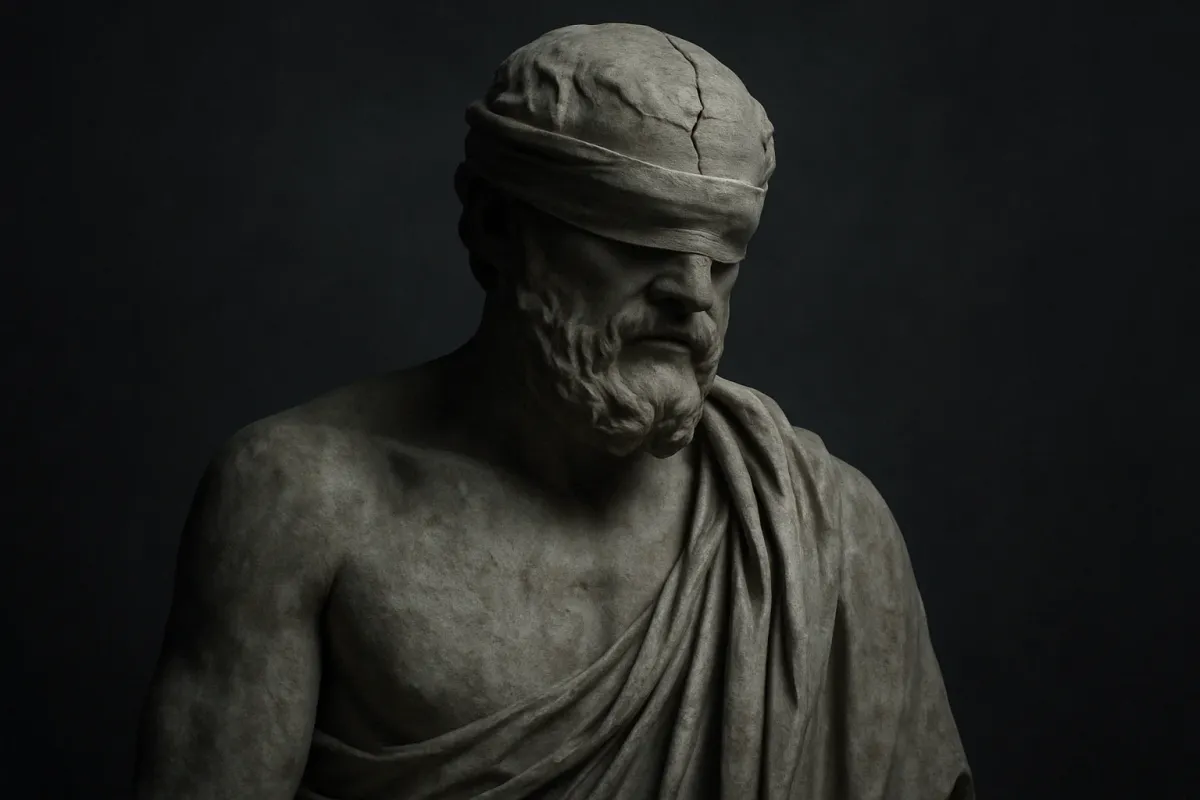

C.S. Lewis, writing decades ago, captured this danger with piercing precision:

“Of all tyrannies, a tyranny sincerely exercised for the good of its victims may be the most oppressive. It would be better to live under robber barons than under omnipotent moral busybodies. The robber baron’s cruelty may sometimes sleep, his cupidity may at some point be satiated; but those who torment us for our own good will torment us without end for they do so with the approval of their own conscience.”

That single line — “the approval of their own conscience” — may be the most chilling. Because the moral busybody does not doubt. They do not ask whether they are right. They are sure. And their certainty gives them licence to intrude into every domain of life, armed not just with laws or policies, but with the unyielding conviction that what they are doing is virtuous. In this model, you are not being punished — you are being helped. You are not being silenced — you are being protected. And if you resist, the problem is not with the authority, but with you.

This is what makes the tyranny of kindness so difficult to resist. It does not feel like tyranny. It feels, at first, like moral progress. It arrives cloaked in empathy, bolstered by consensus, and powered by a kind of social gravity that draws every institution into its orbit. What kind of person, after all, would oppose policies designed to protect the vulnerable? What sort of citizen challenges the moral wisdom of inclusion, safety, and care?

And yet, when virtue becomes dogma, and dogma becomes law, we are no longer reasoning together in a democratic society. We are being managed — often by people who believe that their own ethical clarity gives them the right, indeed the responsibility, to do so.

The irony is that genuine compassion does not seek control. It does not demand unanimity or crush dissent. It does not require that everyone speak the same, think the same, or signal their virtue in precisely the prescribed ways. True empathy invites conversation. It accommodates disagreement, leaving room for the complex and often contradictory reality of human lives.

By contrast, the moral busybody cannot tolerate ambiguity. They see every hesitation as betrayal and every question as sabotage. And because their actions are animated by righteousness rather than realism, there is no natural limit to their reach. The robber baron may eventually be satisfied. The moral reformer never is.

Today, we live with new manifestations of this dynamic. On social media platforms, speech is routinely policed not just for incitement or illegality, but for potential “harm,” a category so elastic it can be stretched to mean virtually anything. In schools and universities, students are taught not how to think critically, but how to affirm a particular moral outlook, often enforced through codes of conduct that blur the line between education and re-education. In law and policy, we see increasingly vague formulations — misinformation, hate speech, psychological safety — invoked to justify interventions that would once have been unthinkable in liberal democracies.

Each of these may be defended in the name of kindness. But the cumulative effect is something far more brittle — a culture where fear replaces curiosity, where moral authority is centralised and unaccountable, and where freedom is not revoked so much as gently escorted out the back door, murmured into submission by people who insist they only want what’s best for you.

Lewis’s warning was not just about politics. It was about the human tendency to mistake our moral intuitions for universal truth. To believe that good intentions guarantee good outcomes. And to forget, fatally, that power exercised with moral certainty is the hardest kind to restrain. Because those who wield it never see themselves as tyrants. They see themselves, always, as saviours.

Further reading

The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis

Lewis explores the loss of objective moral values in modern education and culture — a philosophical foundation for understanding the dangers of moral absolutism cloaked in virtue.

A Conflict of Visions by Thomas Sowell

Sowell outlines the contrasting worldviews that shape political ideologies, helping explain why some believe coercive compassion is a moral imperative.

The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt

Haidt’s work on moral psychology reveals how good people can be divided by politics and religion — and why moral certainty can blind us to our own biases.

Kindly Inquisitors by Jonathan Rauch

A robust defence of free speech and liberal inquiry, Rauch argues that even well-meaning censorship erodes the very foundations of democratic society.

The Parasitic Mind by Gad Saad

Saad critiques ideological possession and emotional reasoning, showing how bad ideas often survive by appealing to virtue rather than truth.

You might also like: