There was a time when moral universalism was the crowning achievement of Western political thought. From the ashes of war and the ruins of tyranny, a fragile but luminous idea emerged: that all human beings possess equal moral worth. That justice must be blind to race, class, nation. That the dignity of the individual is not conferred by circumstance, but inherent. This was not a casual belief. It was hard won. And it came with obligations.

In the writings of Immanuel Kant, this idea was given philosophical structure. Morality, for Kant, was not a matter of preference or sentiment. It was rooted in reason — in the categorical imperative that we act only on principles we would wish to see universalised. This demanded clarity of thought, the refusal of hypocrisy, and a certain moral humility. One could not, for instance, condemn oppression abroad while excusing it at home. One could not preach equality and practise prejudice. The universality of the ethic was its whole point.

But something curious has happened in recent years. The language of moral universalism persists, but the spirit has curdled. The commitment to principle has been replaced by performance. What once demanded reflection and rigour now rewards fluency in the right slogans. As Will Storr has argued, we have entered an age where morality is increasingly a status game — a way not to reason together, but to sort ourselves into castes of the righteous and the damned.

Like where this is going? Get the next article straight to your inbox.

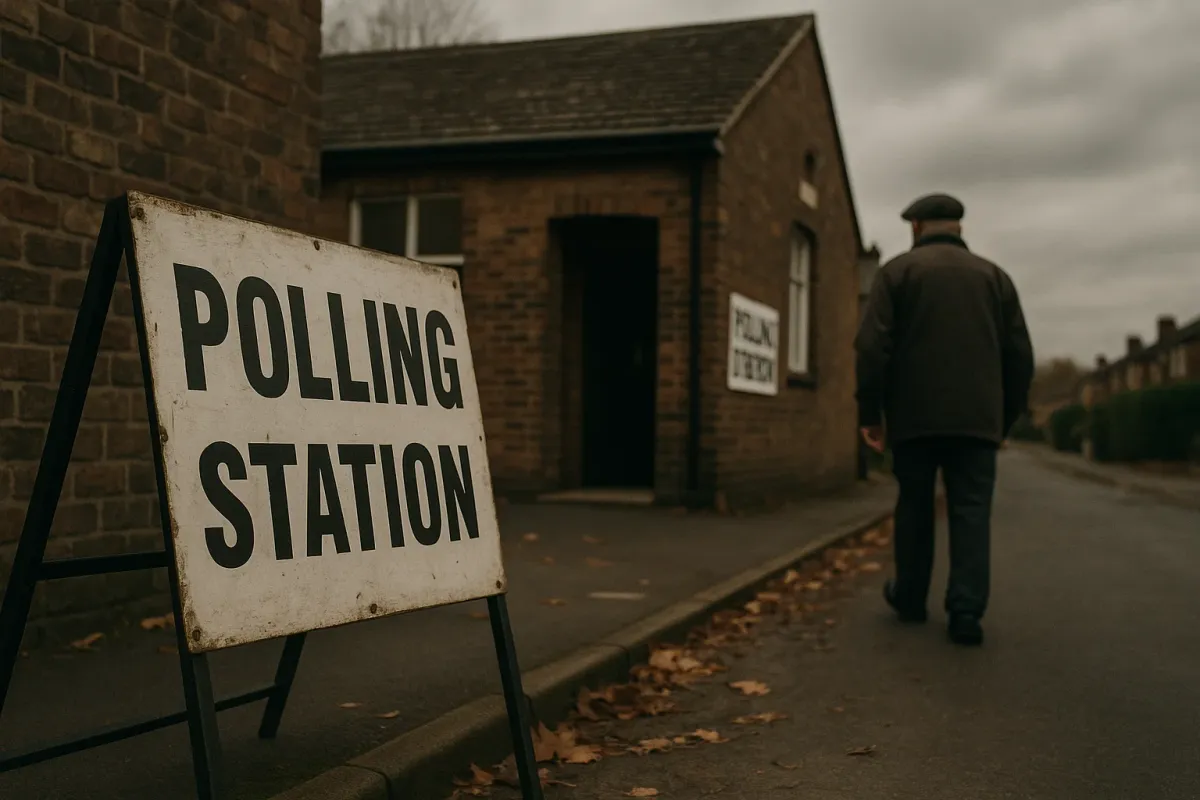

This is especially evident in what is sometimes called hyper-liberalism: a cultural project that speaks in the name of inclusion and justice, but which often reveals a deep unwillingness to hear dissenting voices. Frustration is rebranded as hate. Electoral outcomes are treated as threats to democracy. Those who resist the prevailing narrative are not merely wrong, but morally defective — victims of false consciousness, or worse, deliberate malice. The promise of universal dignity is replaced with the practice of moral exclusion.

And yet the public — in its muddled, contradictory, and imperfect way — senses the dissonance. It sees a political class fluent in the dialect of rights and progress, but seemingly unable to guarantee basic goods: secure borders, affordable energy, coherent public services. It sees institutions that celebrate every identity except national ones. That claim to speak for all, while listening only to a few. That treat working-class anxiety as a problem to be managed, not a voice to be heard.

This is not a rejection of universalism. It is a plea for the real thing.

The philosopher Josef Pieper, drawing on the Christian tradition, spoke of the ordo amoris — the order of the loves. When our loves are disordered, when we prize reputation over truth, image over substance, then even our highest ideals become corrupted. We still speak the language of morality, but we no longer live it. We still talk of equality, but we wield it as a weapon. We still claim to pursue justice, but only when it flatters our tribe.

That is the danger we now face. Not that we have abandoned moral universalism, but that we have hollowed it out — turned it into a costume worn for prestige, a set of talking points to signal alignment, rather than a serious ethic to live by. And in doing so, we invite the very backlash we claim to abhor. Because people can tell the difference between being governed and being managed. Between being heard and being handled.

A society that wants to endure must ground its universalism not in fashion, but in truth. Not in applause, but in duty. And that begins by listening — not just to those who agree with us, but to those we find hardest to hear.

You might also like:

Further reading

The Status Game: On Human Life and How to Play It by Will Storr

An insightful exploration of how much of modern morality is driven by the pursuit of social status — often disguised as virtue or political conviction.

Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals by Immanuel Kant

Kant’s foundational text on moral philosophy, laying out the principles of universal moral law and the dignity of the individual.

Ordo Amoris by Max Scheler

A profound account of the “order of the loves,” examining how moral perception depends on properly oriented desire — and how its distortion leads to ethical confusion.

The Abolition of Man by C.S. Lewis

Lewis’s defence of objective value and warning against the erosion of moral foundations under the guise of progressive relativism.

Reality and the Good: Testing the Foundations of Ethics by Josef Pieper

A compelling philosophical critique of modern ethics, reminding us that truth, not image or ideology, must anchor moral reasoning.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking essays. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.