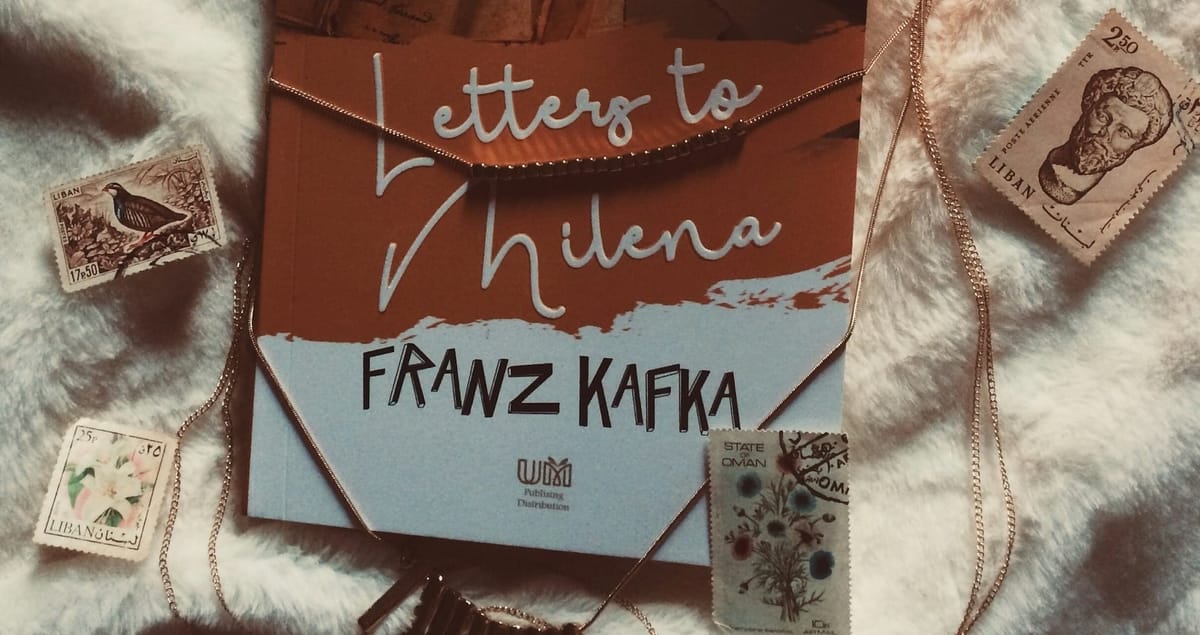

Dystopia rarely arrives with fanfare. It doesn’t march through the gates—it creeps in, disguised as convenience, justified by safety, hidden in the everyday trade-offs of modern life. Fiction gave us warning shots: Orwell imagined fear and surveillance, Huxley envisioned pleasure and passivity, Atwood showed how virtue becomes a weapon. But the world we inhabit doesn’t mirror any single dystopia. It feels like a collage—fragments from different nightmares, stitched together by data, distraction, and the slow erosion of meaning.

We’re not in 1984. We’re not in Brave New World. But we’re living with pieces of both—and more besides.

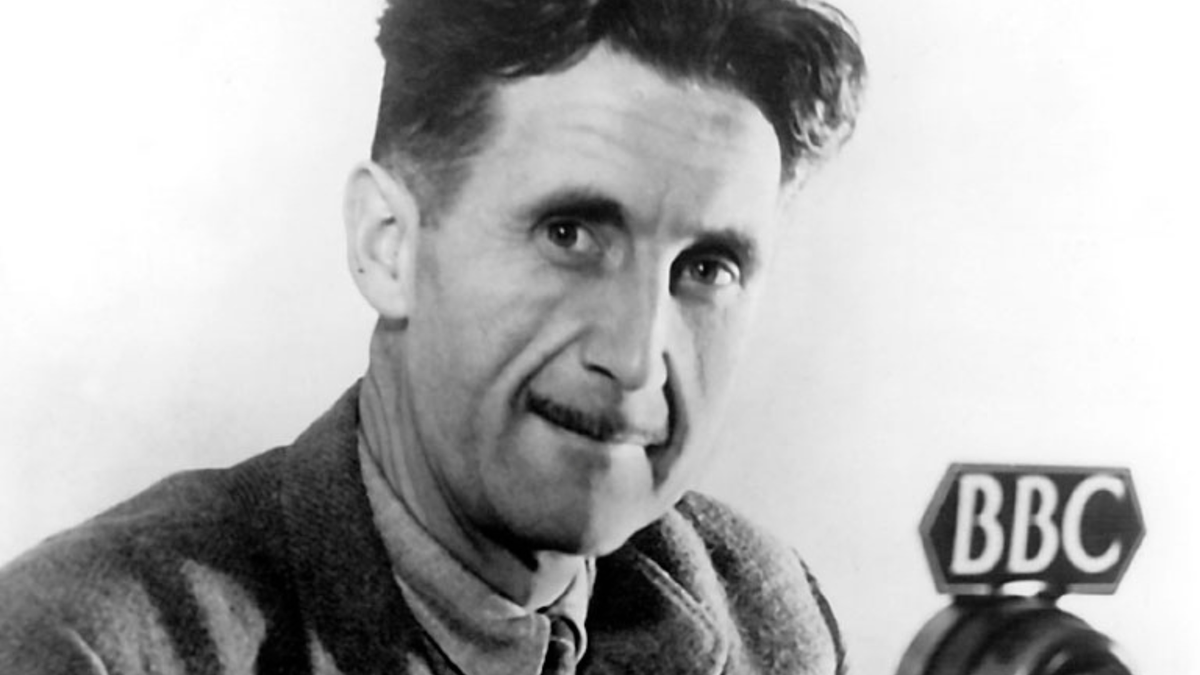

Orwell’s 1984: Surveillance, Misinformation, and the Elasticity of Truth

In Orwell’s world, truth is what the Party says it is. History is rewritten. Dissent is annihilated. The state doesn’t just punish rebellion—it erases the capacity to even imagine it.

Today’s surveillance doesn’t wear jackboots. It comes bearing user agreements. Cities are riddled with cameras. Devices listen. Browsing histories, GPS locations, purchase habits—all silently harvested, sorted, and sold. What Orwell imagined as state oppression now thrives as private-sector efficiency.

Truth, meanwhile, has grown elastic. Orwell’s doublethink—the ability to hold two contradictory ideas at once—now plays out in the theatre of “alternative facts.” Reality bends to tribal narratives. Platforms amplify what flatters, buries what challenges.

We didn’t inherit Orwell’s dystopia. We subscribed to it.

Huxley’s Brave New World: Pleasure as Control

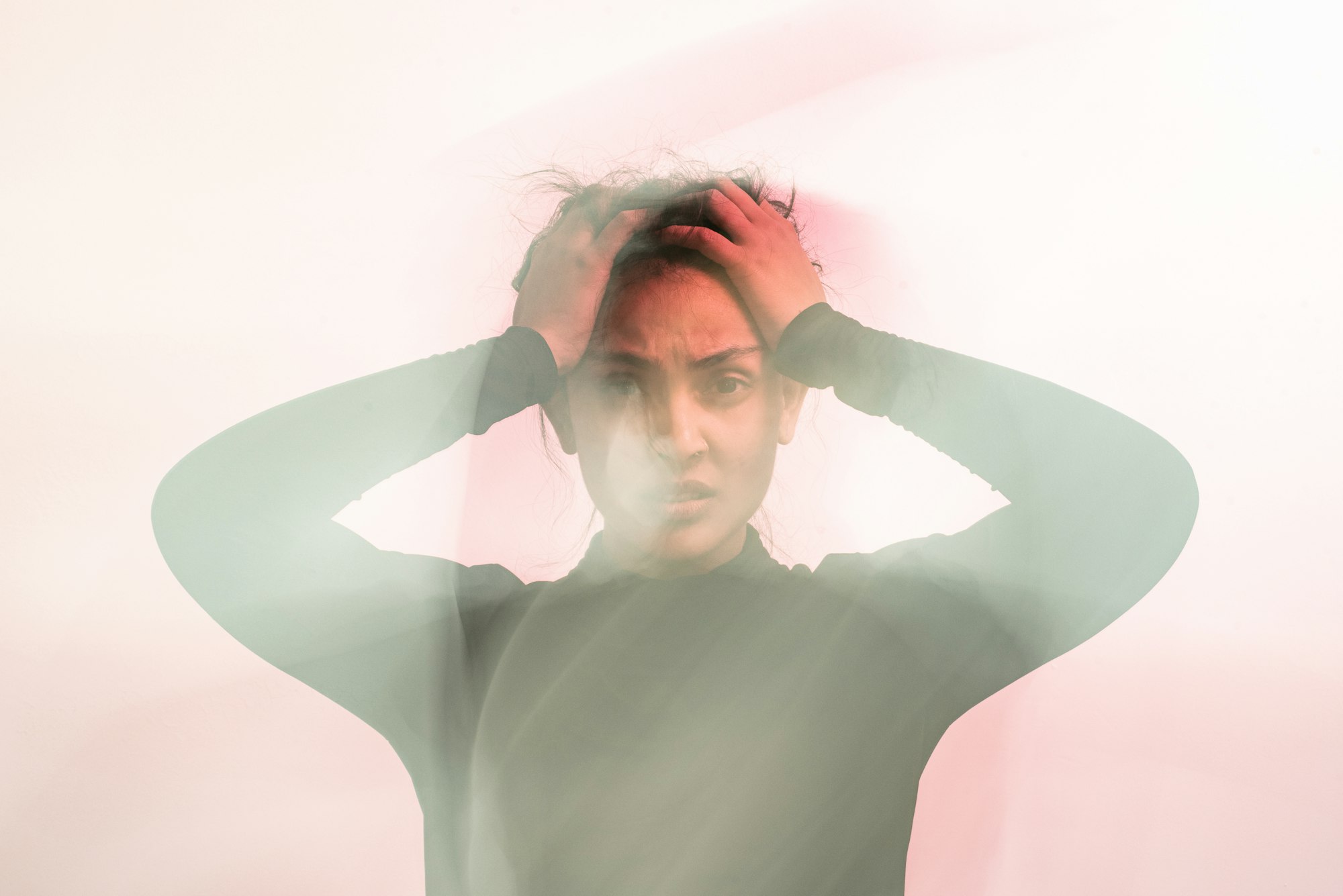

Where Orwell feared pain, Huxley feared pleasure. In his world, people are controlled not by force, but by comfort. Citizens are medicated, entertained, pacified. Conflict is bad taste. Curiosity is a nuisance. Happiness is mandatory.

That society feels less foreign every year. Algorithms spoon-feed us distractions. Scroll loops and dopamine hits turn passivity into a daily ritual. We are not coerced into submission—we choose it, one click at a time.

Consumerism props up the illusion. Endless options give us a sense of freedom while narrowing our capacity to think. The choice isn’t between bread and circuses—it’s between seven brands of circuses, delivered next-day.

Huxley’s nightmare was of a world too comfortable to question itself. We may not take soma, but our numbing agents are digital, curated, and always on.

Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale: Regression by Design

Margaret Atwood didn’t invent Gilead. She reconstructed it. Every law, ritual, and punishment in her theocracy had historical precedent—a chilling reminder that dystopia often arrives dressed in the robes of tradition.

The stripping of rights. The sanctification of power. The enforcement of roles as biological fate. These weren’t imagined. They were remembered.

Today, those warnings feel less speculative and more diagnostic. From legislative rollbacks on reproductive rights to creeping theocratic influence in policy, the past is no longer prologue—it’s policy. Atwood’s brilliance wasn’t in predicting a future. It was in noticing the parts of the past that never went away.

Dystopias They Didn’t Predict

What the great dystopians missed, the 21st century has delivered.

Social credit systems quantify morality. In parts of the world, your access to jobs, travel, even housing is shaped by behaviour scores. Not imposed by decree—but accepted for the sake of order. A bureaucracy of virtue.

Artificial intelligence doesn’t just replace labour. It replaces judgment. Algorithms decide what we see, who we date, which resumes rise, which voices sink. We outsource decisions to code we don’t understand, written by people we don’t see, serving systems we can’t audit.

Digital tribalism fractures us. Not into nations, but into echo chambers. Social media creates not one dystopia but thousands—each with its own facts, enemies, and sacred texts. Division isn’t an accident. It’s an incentive structure.

Gamification turns life into a scoreboard. Fitness apps, work platforms, even dating profiles convert behaviour into metrics. The result? A culture of performative optimisation, where value is defined by streaks, stats, and artificial milestones.

The future didn’t choose a single dystopia. It mashed them together.

Are We Living in a Dystopia?

Not exactly. We’re living in something more insidious—a hybrid. A surveillance state disguised as a convenience economy. A pleasure trap posing as personal freedom. A tribal order masquerading as a global network.

Dystopian fiction wasn’t prophecy. It was diagnosis. A warning flare, not a blueprint. These stories don’t predict—they illuminate. They show us how power cloaks itself. How distraction can become domination. How the collapse of truth begins not with lies, but with indifference.

The question isn’t which dystopia we’re living in. The question is whether we’re paying attention.

You might also like:

Further reading

- Surveillance Capitalism by Shoshana Zuboff.

A deep dive into how data is used to control behaviour.

- Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman.

A perfect companion to Brave New World.

- Enlightenment Now by Steven Pinker.

Advocates for reason, science, and humanism as drivers of progress.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking essays. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.