Roger Scruton remains one of the most thoughtful and provocative thinkers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. A philosopher, writer, and unapologetic defender of conservative thought, he brought something rare to public life: moral seriousness. Scruton wrote about politics and aesthetics, tradition and beauty, but also about the quiet decay of cultural meaning—what he came to describe, implicitly if not always explicitly, as a confrontation with the “nonsense machine.” It’s a phrase that captures, with surgical simplicity, the churn of pseudo-intellectualism, bureaucratic cant, and cultural trend-following that passes for insight in modern life.

To understand what Scruton was pushing back against, one must first understand what he stood for. His work, rooted in a deep respect for tradition, was not nostalgic in the pejorative sense. He was not clinging to the past out of fear, but drawing on it as a source of moral knowledge and aesthetic refinement. Born in 1944, educated at Cambridge, and knighted decades later for his contribution to philosophy and education, Scruton cut a figure that defied the prevailing winds of academia. Where many contemporary thinkers built careers on unravelling the values of the West, Scruton set about defending them—not as dogma, but as inherited wisdom worth preserving.

And this is where the nonsense machine enters the frame.

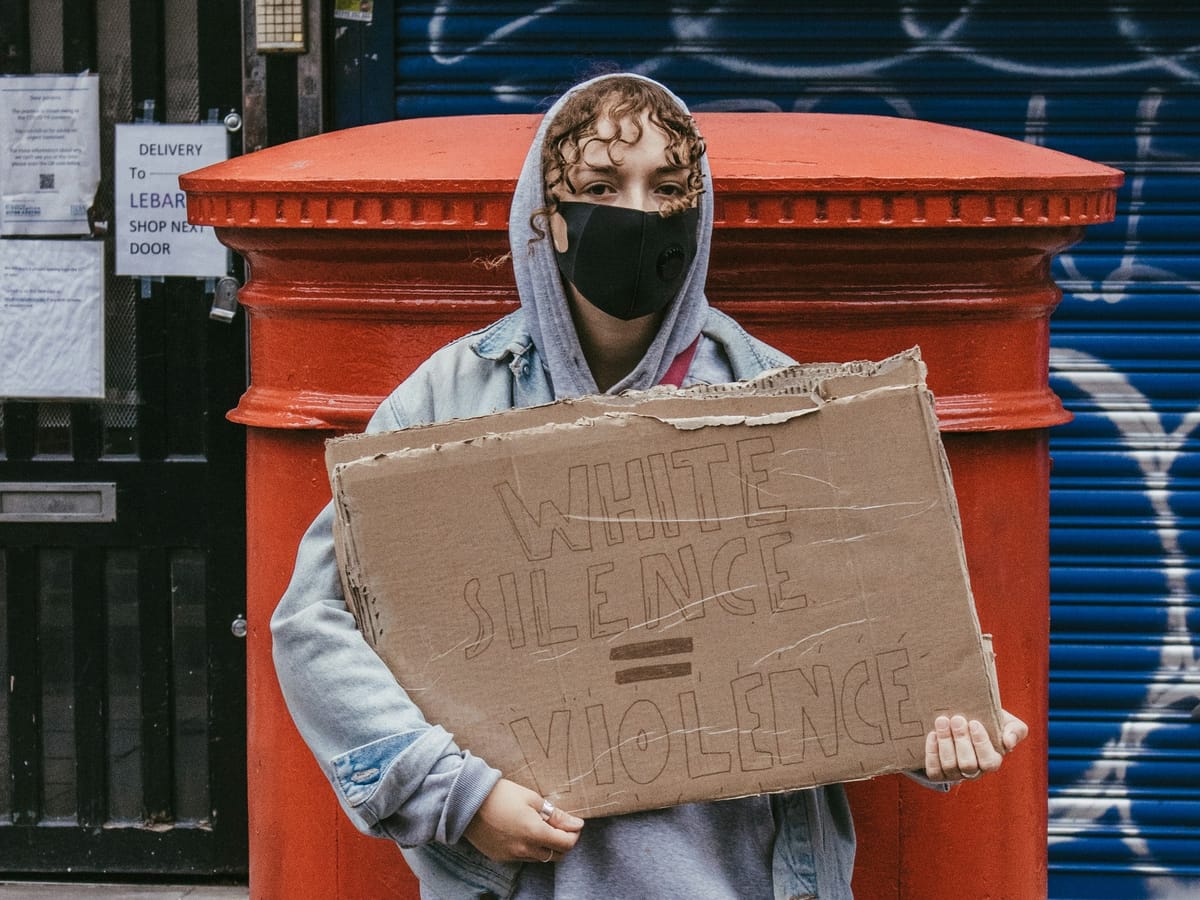

The phrase itself is metaphorical, but the phenomenon is very real. It refers to the cultural machinery—academic, bureaucratic, technological—that transforms thought into performance, reduces inquiry to jargon, and repackages intellectual laziness as moral progress. What the nonsense machine produces is rarely coherent, rarely beautiful, and almost never useful. It relies not on reasoned disagreement but on unearned certainty, and it privileges slogans over arguments, gesture over truth.

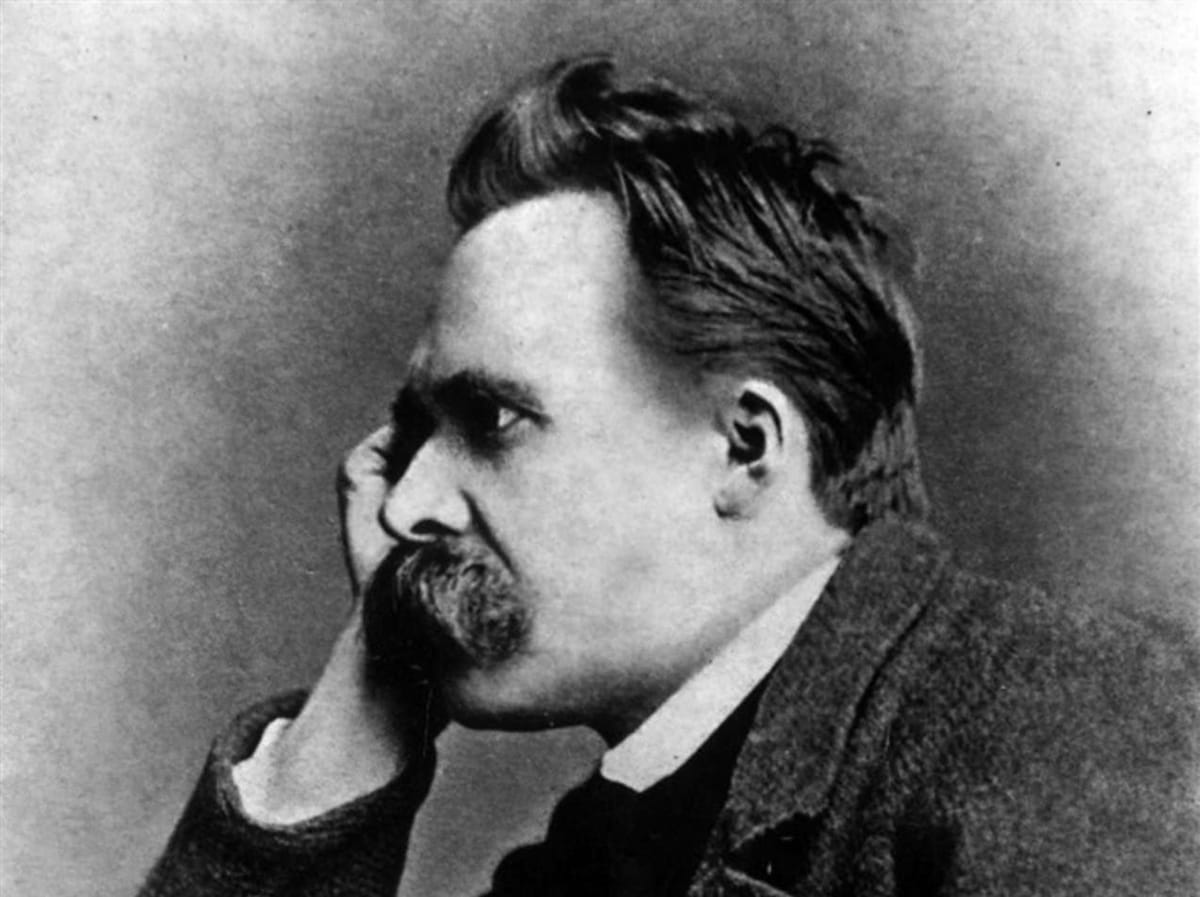

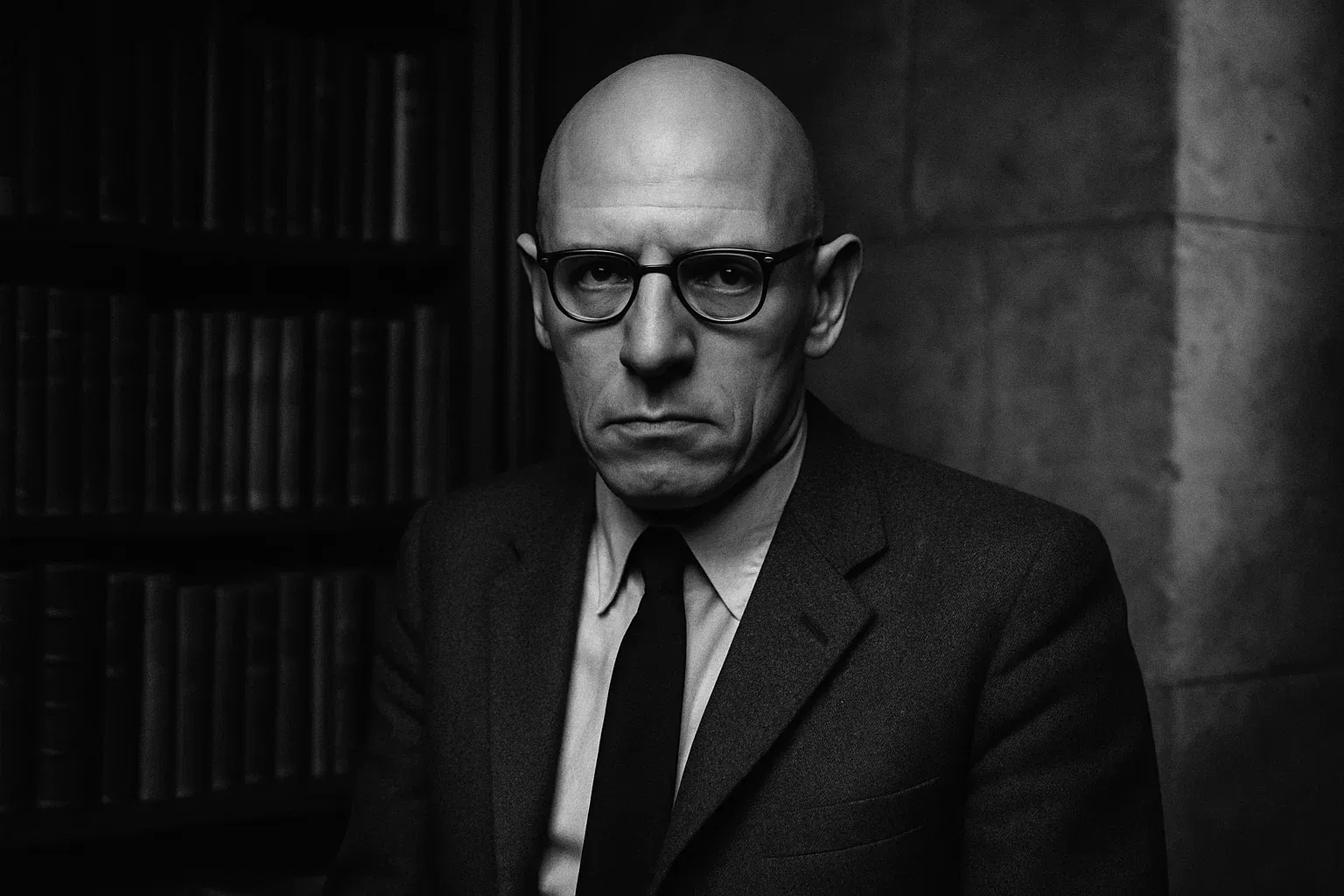

Scruton’s critique of this cultural drift can be found throughout his work, but it is perhaps most pointed in his book Fools, Frauds and Firebrands, in which he takes aim at the fashionable intellectuals of the New Left. Many of these figures, including Michel Foucault, are still revered in humanities departments today, but Scruton saw in them the early signs of decay: a willingness to dismantle truth claims without offering anything coherent in return, a habit of substituting suspicion for understanding. Foucault in particular, with his rejection of objectivity and his framing of all knowledge as a function of power, became emblematic of a deeper problem—what Scruton might have called the replacement of moral reasoning with ideological suspicion.

This is not merely academic. The view that truth is produced by systems of power—and that every claim to knowledge is really a mask for domination—has filtered from seminar rooms into social movements, media commentary, and corporate HR departments. It has shaped a culture in which disagreement is often perceived as harm, persuasion as manipulation, and tradition as oppression. This is not just moral relativism by another name; it’s a worldview that regards any appeal to shared truth as suspect by default.

Scruton’s reply to all this was not reactionary. He did not call for a return to some idealised past. What he argued for—calmly, repeatedly—was the recovery of intellectual humility, aesthetic sensitivity, and moral depth. He believed that beauty, far from being a luxury, is one of the few antidotes to ideological flattening. He saw in traditional forms—be it architecture, music, or ritual—not the oppressive weight of the past, but the accumulated wisdom of generations, offered not as chains but as scaffolding for meaning.

His critique extended beyond philosophy into the lived texture of everyday life. Modern architecture, for example, was for Scruton a perfect expression of the nonsense machine: soulless, utilitarian, performative in its gestures toward progress, but utterly disconnected from place, people, or purpose. The same could be said of much of our political discourse, where gestures of virtue have replaced acts of virtue, and where language is increasingly used to obscure rather than illuminate.

Scruton’s defence of tradition was never absolute. He acknowledged that some customs outlive their usefulness. But he insisted that discarding inherited wisdom without understanding it—on the basis of fashion, theory, or ideology—was an act of vandalism, not progress. He recognised that modernity had brought great benefits, but he warned that when we lose the ability to judge those benefits in moral or aesthetic terms, we risk collapsing into a culture that celebrates novelty for its own sake and mistakes disruption for insight.

What Scruton offers, then, is not just a critique of bad ideas, but a defence of the conditions that make good ideas possible. In a world of fast takes and shallow certainty, his work reminds us that thinking well requires more than cleverness—it requires seriousness, patience, and a willingness to stand apart from the crowd. Against the nonsense machine, he placed the slow work of understanding. Against ideological conformity, the quiet strength of tradition. Against ugliness, beauty.

And against cynicism, hope—not the empty kind, but the kind grounded in things that last.

Further reading

Fools, Frauds and Firebrands by Roger Scruton

Scruton’s incisive critique of leading left-wing intellectuals and the ideas he believed were corroding Western culture from within.

How to Be a Conservative by Roger Scruton

A clear, accessible articulation of Scruton’s political philosophy, rooted in tradition, responsibility, and the defence of inherited wisdom.

Beauty: A Very Short Introduction by Roger Scruton

A compact but profound reflection on why beauty matters — and what its decline tells us about the modern world.

Explaining Postmodernism by Stephen Hicks

A critical overview of the philosophical shift from reason to relativism, with a sharp lens on Foucault and other postmodern figures Scruton challenged.

Moral Relativism by Steven Lukes

A balanced examination of moral relativism — its appeal, its dangers, and its implications for truth and tolerance.

Why Beauty Matters (BBC Documentary, 2009) by Roger Scruton — YouTube

A deeply moving visual essay in which Scruton defends beauty against modern ugliness, explaining its spiritual and civilisational significance.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking articles. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.

You might also like: