A few months ago, UWC Atlantic, an independent school in South Wales founded by a refugee from Nazi Germany, invited Jewish journalist Jonathan Sacerdoti to speak to its students about antisemitism and journalism. Within days, the school rescinded the invitation. The reason? Some students had reportedly argued that his presence would be "distressing."

Sacerdoti hadn’t been planning to deliver a diatribe. He wasn’t coming to shout or provoke. He had simply been asked to speak about his lived experience of anti-Jewish prejudice, and the role of journalism in shaping public discourse. But that, apparently, was too much.

This wasn’t an isolated case. Across the Western world, institutions increasingly find themselves caught between the twin pressures of ideological zeal and liberal ideals. They want to be inclusive, to show tolerance.

But in their eagerness to avoid offence, they sometimes silence thoughtful, measured voices—while giving platforms to ideas that are not merely controversial, but corrosive.

Think better. Get the FREE guide.

Join Veridaze and get 10 Mental Tools for Clearer Thinking — a free guide to cutting through noise, confusion, and nonsense.

Take UN Women, for instance, which in late 2023 posted a tweet mourning the deaths of women and children in Gaza without any mention of the Israeli women raped and murdered by Hamas just weeks earlier. After a global outcry, the tweet was deleted. But it revealed a troubling trend: the selective moral outrage of institutions that, in theory, exist to defend universal human rights.

Here lies the paradox: in the name of openness, we risk opening the gates to extremism. In the name of free speech, we may end up silencing others—not through legislation, but through fear, through intimidation, through the normalisation of hate disguised as “dissent.”

Karl Popper warned us about this in 1945. Unlimited tolerance, he argued, leads to the disappearance of tolerance itself. If those who preach hate are permitted to operate unchecked—if their ideology is given equal footing with reasoned debate—they will, in time, destroy the very freedoms that allowed them to speak.

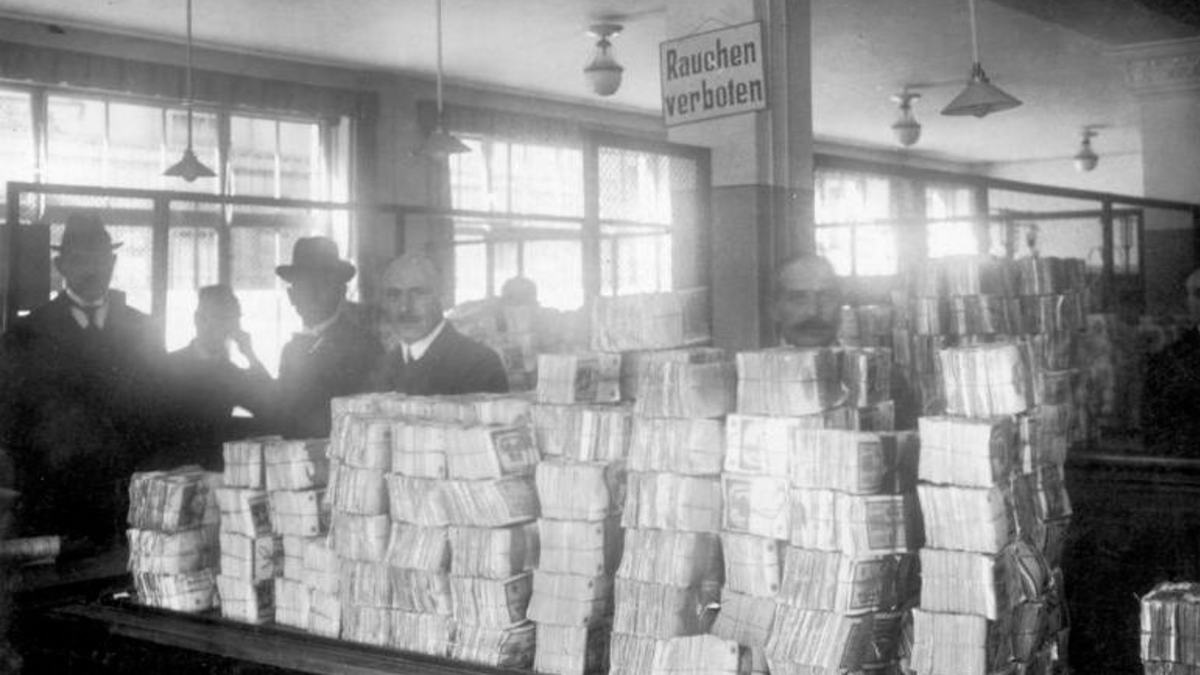

This is not abstract theory. It is historical fact. The Nazis were voted into power. Lenin rose under the banner of revolution and liberty. The Ayatollah overthrew a tyrant—and became one. In each case, a society that refused to draw moral boundaries invited its own collapse.

And yet today, drawing lines is seen by many as an act of oppression. Say that certain ideologies are incompatible with liberal democracy, and you're accused of being intolerant. Push back against decolonisation narratives that erase Jewish history, and you're branded a racist. Argue that men cannot become women, and you may find yourself sacked, silenced, or sent to diversity training.

This is not the mark of a confident, liberal society. It is the mark of a culture so anxious to avoid offence that it forgets what it stands for.

Popper didn’t argue for censorship in the crude, authoritarian sense. He believed in argument, dialogue, persuasion. But he also recognised that some ideologies are not interested in dialogue. They do not seek to co-exist; they seek to dominate. And when they do, liberal societies must have the moral courage to say: no. Not here.

This isn’t intolerance. It’s defence.

A mature democracy must be able to distinguish between disagreement and delegitimisation. Between unpopular opinions and dangerous ideologies. Between the open-mindedness of reason and the moral vacuum of relativism.

We can—and must—hold the line. Not to exclude voices for the sake of comfort, but to protect the conditions under which debate, discovery, and freedom can flourish.

Because sometimes, the most tolerant thing a society can do… is say no.

Further reading

The Open Society and Its Enemies – Karl Popper

Popper’s seminal work laying out the dangers of totalitarianism — and the foundational idea of the "paradox of tolerance."

Liberalism and Its Discontents – Francis Fukuyama

A timely reflection on how liberal democracies are being destabilised from within by illiberal movements across the spectrum.

The Madness of Crowds – Douglas Murray

A provocative examination of identity politics and the new intolerance that masquerades as progressivism.

The Righteous Mind – Jonathan Haidt

Explores why good people are divided by politics and religion, and how understanding moral psychology can help rebuild mutual respect.

Can We Be Free? – Quentin Skinner

A short but powerful philosophical inquiry into what freedom actually means — and how it depends on civic virtue and restraint.

If you found this useful, consider subscribing for more thought-provoking articles. And feel free to share your take in the comments below.

You might also like: